‘Exploring Tritium’s Danger’: a book review

The Braidwood nuclear power plant rises above nearby homes. The state of Illinois and Will County officials sued the owners and operators of the facility in 2006, claiming they failed to report leaks of radioactive tritium from the facility. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Over the past 40 years, Arjun Makhijani has provided clear, concise, and important scientific insights that have enriched our understanding of the nuclear age. In doing so, Makhijani—now president of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research—has built a solid reputation as a scientist working in the public interest. His most recent contribution to public discourse, Exploring Tritium’s Dangers, adds to this fine tradition.

A radioactive isotope of hydrogen, tritium is one the most expensive, rare, and potentially harmful elements in the world. Its rarity is underscored by its price—$30,000 per gram—which is projected to rise from $100,000 to $200,000 per gram by mid-century.

Although its rarity and usefulness in some applications gives it a high monetary value, tritium is also a radioactive contaminant that has been released widely to the air and water from nuclear power and spent nuclear fuel reprocessing plants. Makhijani points out that “one teaspoon of tritiated water (as HTO) would contaminate about 100 billion gallons of water to the US drinking water limit; that is enough to supply about 1 million homes with water for a year.”

Where tritium comes from. Since Earth began to form, the radioactive isotope of hydrogen known as tritium (H-3) has been created by interactions between cosmic rays and Earth’s atmosphere; through this natural process, the isotope continues to blanket the planet in tiny amounts. With a radioactive half-life of 12.3 years, tritium falls from the sky and decays, creating a steady-state global equilibrium that comes to about three to seven kilograms of tritium.

Tritium initially became a widespread man-made contaminant when it was spread across the globe by open-air nuclear weapons explosions conducted between 1945 and 1963. Rainfall in 1963 was found in the Northern Hemisphere to contain 1,000 times more tritium than background levels. Open-air nuclear weapons explosions released about 600 kilograms (6 billion curies) into the atmosphere. In the decades since above-ground nuclear testing ended, nuclear power plants have added even more to the planet’s inventory of tritium. For several years, US power reactors have been contaminating ground water via large, unexpected tritium leaks from degraded subsurface piping and spent nuclear fuel storage pool infrastructures.

Since the 1990s, about 70 percent of the nuclear power sites in the United States (43 out of 61 sites) have had significant tritium leaks that contaminated groundwater in excess of federal drinking water limits.

The most recent leak occurred in November 2022, involving 400,000 gallons of tritium-contaminated water from the Monticello nuclear station in Minnesota. The leak was kept from the public for several months. In late March of this year, after the operator could not stop the leak, it was forced to shut down the reactor to fix and replace piping. By this time, tritium reached the groundwater that enters the Mississippi River. A good place to start limiting the negative effects of tritium contamination, Makhijani recommends, is to significantly tighten drinking water standards.

Routine releases of airborne tritium are also not trivial. As part of his well-researched monograph, Makhijani underscores this point by including a detailed atmospheric dispersion study that he commissioned, indicating that tritium (HTO) from the Braidwood Nuclear Power Plant in Illinois has been literally raining down from gaseous releases – as it incorporates with precipitation to form tritium oxide (HTO)—something that occurs at water cooled reactors. Spent fuel storage pools are considered the largest source of gaseous tritium releases.

The largely unacknowledged health effects. Makhijani makes it clear that the impacts of tritium on human health, especially when it is taken inside the body, warrant much more attention and control than they have received until now. This is not an easy problem to contend with, given the scattered and fragmented efforts that are in place to address this hazard. Thirty-nine states, and nine federal agencies (the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of Energy (DOE), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Department of Agriculture are all responsible for regulating tritium.

This highly scattered regulatory regime has been ineffective at limiting tritium contamination, much less reducing it. For example, state and federal regulators haven’t a clue as to how many of some two million exit signs purchased in the United States—and made luminous without electric power by tritium—have been illegally dumped. For decades, tritium signs, each initially containing about 25 curies (or 25,000,000,000,000 pCi) of radioactivity, have found their way into landfills that often contaminate drinking water. One broken sign is enough to contaminate an entire community landfill. There are no standards for tritium in the liquid that leaches from landfills, despite measurements taken in 2009 indicating levels at Pennsylvania landfills thousands of times above background.

Adding to this regulatory mess, is the fact that federal standards limiting tritium in drinking water only apply to public supplies, and not to private wells.

In past decades, regulators have papered over the tritium-contamination problem by asserting, when tritium leakage becomes a matter of public concern, that the tritium doses humans might receive are too small to be of concern. Despite growing evidence that tritium is harmful in ways that fall outside the basic framework for radiation protection, agencies such as the Nuclear Regulatory Commission remain frozen in time when it comes to tritium regulation.

The NRC and other regulating agencies are sticking to an outdated premise that tritium is a “mild” radioactive contaminant that emits “weak” beta particles that cannot penetrate the outer layers of skin. When tritium is taken inside the body (by, for example, drinking tritiated water), half is quickly excreted within 10 days, the agencies point out, and the radiation doses are tiny. Overall, the NRC implies its risk of tritium ingestion causing cancer is small.

But evidence of harm to workers handling tritium is also growing. Epidemiologists from the University of North Carolina reported in 2013, that the risk of dying from leukemia among workers at the Savannah River Plant following exposure to tritium is more than eight times greater (RBE-8.6) than from exposure to gamma radiation (RBE-1). Over the past several years, studies of workers exposed to tritium consistently show significant excess levels of chromosome damage.[1]

The contention that tritium is “mildly radioactive” does not hold when it is taken in the body as tritiated water—the dominant means for exposure. The Defense Nuclear Facility Safety Board—which advises the US Energy Department about safety at the nation’s defense nuclear sites—informed the secretary of energyin June 2019 that “[t]ritiated water vapor represents a significant risk to those exposed to it, as its dose consequence to an exposed individual is 15,000 to 20,000 times higher than that for an equivalent amount of tritium gas.”

As it decays, tritium emits nearly 400 trillion energetic disintegrations per second. William H. McBride, a professor of radiation oncology at the UCLA Medical School, describes these disintegrations as “explosive packages of energy” that are “highly efficient at forming complex, potentially lethal DNA double strand breaks.” McBride, underscored this concern at an event sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, where he stated that “damage to DNA can occur within minutes to hours.” [2]

“No matter how it is taken into the body,” a fact sheet from the Energy Department’s Argonne National Laboratory says, “tritium is uniformly distributed through all biological fluids within one to two hours.” During that short time, the Defense Nuclear Facility Safety Board points out that “the combination of a rapid intake and a short biological half-life means a large fraction of the radiological dose is acutely delivered within hours to days…”

A new approach to tritium regulation. Makhijani pulls together impressive evidence clearly pointing to the need for an innovative approach that addresses, in addition to cancer, a range of outcomes that can follow tritium exposure, including prenatal and various forms of genomic damage. In particular, he raises a key point about how physics has dominated radiation protection regulation at the expense of the biological sciences.

It all boils down to estimation of a dose as measured in human urine based on mathematical models. For tritium, dose estimation can be extraordinarily complex (at best) when it is taken inside the body as water or as organically bound, tritide forms. So the mathematical models that can simplify this challenge depend on “constant values” that provide the basis for radiation protection.

In this regard, the principal “constant value” holding dose reconstruction and regulatory compliance together is the reliance on the “reference man.” He is a healthy Caucasian male between the age of 20 to 30 years, who exists only in the abstract world.

Use of the reference man standard gives rise to obvious (and major) questions: What radiation dose limit is necessary to protect the “reference man” from serious genomic damage? And what about protection of more vulnerable forms of human life?

According to the 2006 study by the National Research Council, healthy Caucasian men between the age of 20 and 30 are about one-tenth as likely to contract a radiation-induced cancer as a child exposed to the same external dose of gamma radiation while in the womb.

In his monograph, Makhijani underscores the need to protect the fetus and embryo from internal exposures to tritium—a need largely being side-stepped by radiation protection authorities. “Tritium replaces non-radioactive hydrogen in water, the principal source of tritium exposure,” Makhijani writes, pointing to unassailable evidence that tritium “easily can cross the placenta and irradiate developing fetuses in utero, thereby raising the risk of birth defects, miscarriages, and other problems.”

He is not alone in such an assessment. According a 2022 medical expert consensus report on radiation protection for health care professionals in Europe, “The greatest risk of pregnancy loss from radiation exposure is during the first 2 weeks of pregnancy, while between 2-8 weeks after conception, the embryo is most susceptible to the development of congenital malformations because this is the period of organogenesis.”

In the United States, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s efforts to reduce exposure limits and protect pregnant women and their fetuses is best described as foot-dragging. By comparison, the required limit for a pregnant worker in Europe to be reassigned from further exposure is one-fifth the US standard—and was adopted nearly 20 years ago.

Long-term environmental retention. A 2019 study put forward the first ever empirical evidence of very long-term environmental retention of organically bound tritium (OBT) in an entire river system, deposited by fallout from atmospheric nuclear weapons explosions.

When released into the environment, tritium atoms can replace hydrogen atoms in organic molecules to form organically bound tritium, which is found soil, and river sediments, vegetation, and a wide variety of foods. It’s been more than a half century since the ratification of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, and tritium released through nuclear weapons testing has undergone significant decay. Yet because of the long retention of organically bound tritium, in greater than expected concentrations, it still remains a contaminant of concern.

For instance, despite its 12.3-year half-life, a much larger amount of organically bound tritium from nuclear tests than previously assumed is locked in Arctic permafrost, raising concerns about widespread contamination as global warming melts the Arctic. Organically bound tritium can reside in the body far longer than tritiated water, to consequently greater negative effect.[3]

Nuclear weapons, nuclear power, and tritium. The tritium problem has several dimensions that relate directly to the world’s current and future efforts vis a vis nuclear power and nuclear weapons.

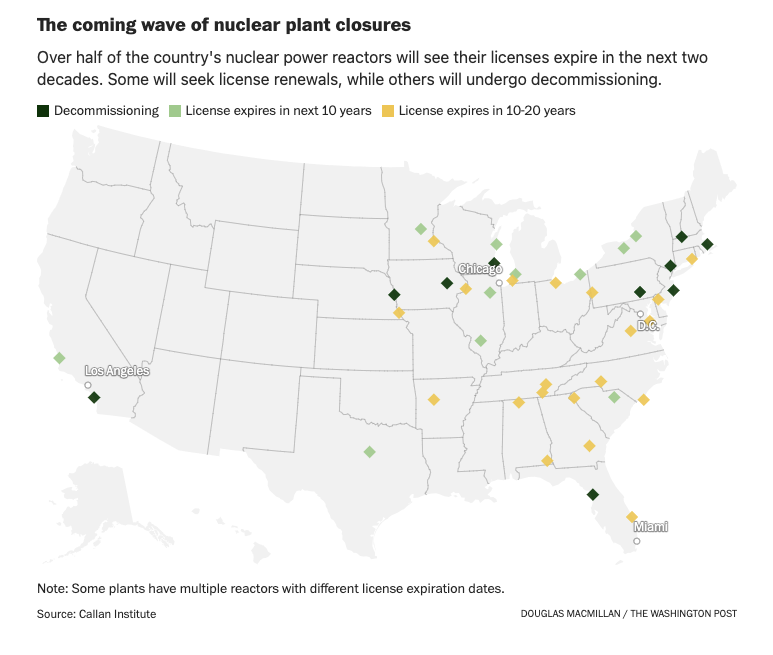

Now that nuclear power reactors are closing down, especially in the aftermath of the Fukushima accident, the disposal of large volumes of tritium-contaminated water into lakes, rivers, and oceans is becoming a source of growing concern around the world. The Japanese government has approved the dumping of about 230 million gallons of radioactive water, stored in some 1,300 large tanks sitting near the Fukushima nuclear ruins, into the Pacific Ocean. Once it incorporates into water, tritium is extraordinarily difficult, if not impossible to remove.

Protests in Japan by a wide segment of the public and in several other nations—including Russia, the Marshall Islands, French Polynesia, China, South Korea and North Korea—object to the disposal of this large volume of contaminated water into near-shore waters.

Then there’s the matter of boosting the efficiency and destructive power of nuclear weapons with tritium gas—a use that has dominated demand for this isotope. Because five percent of the tritium in thermonuclear warheads decays each year, it has to be periodically replenished. Over the past 70 years, an estimated 225 kilograms of tritium were produced in US government reactors, principally at the Savannah River Plant in South Carolina. Those reactors were shuttered in 1988. Since 2003, tritium supplies for US nuclear warheads are provided by two Tennessee Valley Authority nuclear power reactors. The irradiation of lithium target elements in the reactors has fallen short of meeting demand because of excess tritium leakage into the reactor coolant.

The hazards of tritium production for weapons are far from trivial.

For instance, since June of 2019, the Defense Nuclear Facility Safety Board has taken the Energy Department to task for its failure to address the risk of a severe fire involving tritium processing and storage facilities at the Savannah River Site. According to the Board, such a fire may have a 40 percent chance of occurring during 50 years of operation and could result in potentially lethal worker doses greater than 6,000 rems—1,200 times the annual occupational exposure limit. Doses to the public would not be inconsequential. Meanwhile, the Energy Department is under pressure from the nuclear weapons establishment to step up demand for tritium. Unless there is “a marked increase in the planned production of tritium in the next few years,” the 2018 US Nuclear Posture Review concluded “our nuclear capabilities will inevitably atrophy and degrade below requirements.”

The Energy Department estimates it will take 15-20 years to achieve a major multibillion overhaul of its tritium production infrastructure.

Meanwhile, the quest for fusion energy highlights a startling fact: The amount of tritium required to fuel a single fusion reactor (should an economic, fusion-based power plant ever be created) will likely be far greater than the amount produced by all fission reactors and open-air bomb tests since the 1940s. A full-scale (3,000 megawatt-electric) fusion reactor is estimated to “burn” about 150 kilograms of tritium a year.[4]

The cost for a one-year batch of tritium fuel for a fusion reactor, based on the current market price, would be $4.5 billion. An annual loss to the environment from a single fusion reactor could dwarf the release of tritium from all nuclear facilities that currently dot the global landscape.

The tritium overview. Evidence is mounting not just in regard to increased health risks from tritium-contaminated water and from organically bound tritium, but also as relates to the harm tritium can visit on the unborn. At the same time, it has become clear that regulation of tritium in the United States is grossly insufficient to the current risk from tritium contamination, not to mention future risks that could arise if tritium production, use, and associated leakage rise. Arjun Makhijani provides a useful roadmap for sparing workers and the public from the dangers this pernicious contaminant will pose in the future, absent more effective regulation that includes lower limits for human tritium exposure.

Notes

[1] See: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s004200050272; https://www.mdpi.com/2305-6304/10/2/94; https://www.jstor.org/stable/3579658; http://www.rbc.kyoto-u.ac.jp/db/Literature/THO-Occupational.html; and https://www.unscear.org/docs/publications/2016/UNSCEAR_2016_Annex-C.pdf

[2] William MacBride, UCLA School of Medicine Vice Chair for Research in Radiation, Principal Investigator of UCLA’s Center for Medical Countermeasures Against Radiation — National Institutes of Health, Jan 27, 2014. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XEH72v-yN9A

[3] See https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-47821-1

[4] Advocates assume that only the initial loading of 150 kg will be needed, as the reactor will “breed” the remaining amount of tritium to run the plant after a year of operation.

Preview YouTube video Nuclear Watch: Radiation and nuclear countermeasures program overview 1/27/2014

Nuclear Watch: Radiation and nuclear countermeasures program overview 1/27/2014

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/36TAJLFWGJCDFKZL72GFLEDEXM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/AVV56NZXHNFZVAF55WQ3UYAVUA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/YS7REXZOM5BQ7IKNFY3ZTHS4NQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/3SDAQ27NINBP3CPRZKGCHMDHXI.jpg)

By

By